The Republicans’ Main Talking Point Against Drug Price Negotiations Comes From a Pharmaceutical Investor

The claim has been spread by congressional leaders and major news outlets with no mention of the author's corporate ties.

By Donald Shaw and David Moore, Sludge

On Tuesday, following the Biden administration’s announcement of the pharmaceutical drugs that it has chosen for Medicare price negotiations under the Inflation Reduction Act, the Republican leaders of three congressional committees released a document attacking the plan. Citing research from the University of Chicago, the Republicans’ document says the program will “derail and destroy current and future drug development” and result in “135 fewer new drugs.”

The document was endorsed by House Ways and Means Chairman Jason Smith (R-Mo.), House Energy and Commerce Committee Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.), and Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Mike Crapo (R-Idaho), but it’s just the latest example of congressional Republicans warning about 135 fewer new drugs coming to market. In October of last year, for example, Sen. James Lankford (R-Okla.) cited the figure in a press release, and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) referenced it in his September 2022 “Commitment to America” platform.

The University of Chicago study’s prediction of 135 fewer drugs through 2039 is much greater than what nonpartisan government researchers have estimated. According to a July 2022 analysis by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provision is expected to lead to 15 fewer new drugs over a 30-year period, and just one fewer drug over the next decade. The University of Chicago study itself notes in the abstract that its estimated effects on new drugs are 27 times greater than what CBO had determined.

The study gives Republicans a way to echo the pharmaceutical lobby’s main talking point against Medicare price negotiations without referencing their research. The top industry trade association, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), equates the IRA’s negotiation program to “government price setting” and says most of its member companies expect it to have “substantial impacts” on their R&D decisions in the areas of cardiovascular, mental health, neurology, infectious disease, cancer, and rare diseases.

While the Republicans are always sure to give the study credibility by saying it was produced by a university, what’s never said is that its two authors are former Trump administration officials and that one of them has deep financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry.

Co-author Tomas J. Philipson was a member of President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers from August 2017 to June 2020, serving as an acting chairman of the body for the final year of his tenure. During his time on the Council of Economic Advisers, the group published a report that said that a public health care system like Medicare for All would provide worse care than the current system, and another that concluded that Trump’s regulatory rollbacks would boost household incomes by $3,100 per year, according to the Washington Post. After leaving the Trump administration, Philipston founded the Initiative on Enabling Choice and Competition in Health Care at the University of Chicago, a program that was seeded by a nearly $500,000 grant from the Charles Koch Foundation.

The paper’s other co-author was Troy Durie, who was a staff economist at the Council of Economic Advisers before joining the University of Chicago Economics Department in January 2021.

While he was in the Trump White House, Philipson’s research center was being funded by the Charles Koch Foundation, as well as Pfizer. Philipson and his institute co-leader, economist Casey Mulligan, launched the Health Economics Initiative at the University of Chicago’s Becker Friedman Institute. The research center’s funders include the Koch group and the pharmaceutical giant, according to its annual reports, and the duo’s research continued to be lauded by the Koch group as of the end of last year. Philipson was the director of the program as of June 2018, according to a press release.

Together with two other academics, Philipson founded a healthcare consulting firm called Precision Health Economics in 2006 that worked for drug companies including Gilead, Pfizer, and AbbVie, plus industry trade group PhRMA. In a 2017 profile, “Big Pharma Quietly Enlists Leading Professors to Justify $1,000-Per-Day Drugs,” ProPublica described Philipson and his colleagues as taking the conflicts between their scholarly and commercial roles to the next level, and rarely disclosing their financial entanglements.

Precision Health Economics was sold in 2015, but Philipson still maintains many ties to the industry. He is currently an investor and advisor with MEDA Angels, a healthcare angel investor group that has two dozen companies in its portfolio, and an active fund raising $2 million. Its portfolio companies include biopharmaceutical startups, precisely the types of companies that could be impacted by the IRA, since more established drugs that have generic or biosimilar competitors on the market are not eligible for Medicare negotiations. These companies include NuvOx Pharma, which has multiple drugs in its clinical pipeline for addressing cancer and strokes, and Eipbone, which is developing drugs for skeletal repair.

Philipson is also on the board of directors of pharmaceutical startup companies Biologix, which manufactures insulin, and Epigenetix, which is developing cancer treatment drugs. In addition, he sits on the Scientific and Medical Advisor Board of the AI medicine platform company GATC Health, which “simulates human biochemistry’s billions of interactions for novel target identification, drug discovery and development, and rapid disease prediction.”

It’s not just congressional Republicans who are citing Philipson and Durie’s findings without disclosing the authors’ political backgrounds and pharmaceutical ties. Just yesterday, the Wall Street Journal editorial board cited the study in its article opposing the program, and conservative think tanks including Heritage Foundation, American Action Forum, Citizens Against Government Waste, and Americans for Prosperity referenced the study in their posts against the IRA program. The figure of 135 treatments also received mention in Newsweek, The Hill, Forbes, and local newspapers.

Besides opposing the IRA negotiations, House Republicans are also opposing bills in Congress from Democratic Sens. Amy Klobuchar (Minn.) and Peter Welch (Vt.) that would expand the program to cover more drugs and make drugs eligible for negotiations after 5 years on the market, instead of the 9 required by the IRA. In opposing that proposal, House Republicans on the Budget Committee published a document in July citing a figure from a group called We Work For Health, claiming that it would lead to 237 fewer drugs coming to market over the next ten years. We Work For Health is an advocacy group that was founded by PhRMA and drug companies, according to documents discoverable online from its PR firm 720 Strategies, that describes itself as “a grassroots initiative that shows how biopharmaceutical research and medical innovation work together.” PhRMA gave it a $11.7 million grant in 2021, providing about 95% of its funding that year. The PhRMA affiliation does not appear to be disclosed on the We Work For Health website.

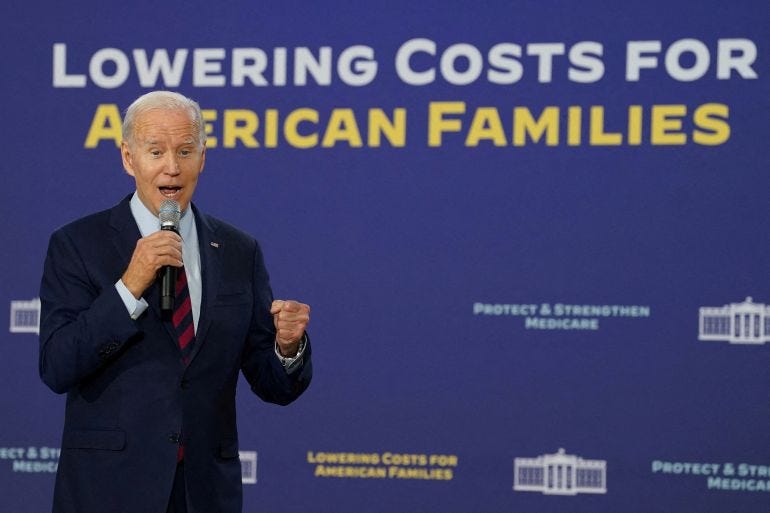

The Biden administration this week announced the ten drugs that will be up for price negotiations with Medicare. They include psoriasis treatment Stelara, made by Janssen Biotech, diabetes medication Farxiga, from AstraZeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novo Nordisk’s NovoLog, an insulin injection treatment. The lower negotiated prices for these drugs will be available for Medicare beginning in September 2026, unless the program is halted before then.

A tracking poll from health policy organization KFF has consistently found broad support for the Medicare drug pricing reforms, including 89% of Democrats and 77% of Republicans.

Six drug companies including Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and Bristol Myers Squibb, as well as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Infusion Center Association, have sued in federal court to stop the IRA program and are threatening to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Trade group PhRMA, which represents giants Eli Lilly and Pfizer among others, sued the Biden administration as well to block the plan, calling the negotiations unconstitutional.

Researchers have found reason to contest the pharma industry’s arguments that drug innovation would need to be stifled if prices for certain highly prescribed treatments are negotiated. A recent study by economists at the University of Massachusetts and Brown University found that more than a dozen large pharmaceutical companies spent around $87 billion more on stock buybacks and dividends than they did on research and development from 2012 to 2021.

The pharmaceutical industry’s playbook to obscure its role in the high prices of prescribed drug treatments also includes ad spending that deflects blame onto other healthcare industries like hospitals and insurers. As of earlier this year, PhRMA had already shelled out more than $9 million on ad campaigns blaming health insurers and others for inflating the price of medicine. According to data from the Facebook Ad Library, PhRMA has also splurged on more than $4 million in ads on the platform since the IRA was signed into law, many of which accuse hospitals and pharmacy benefit managers of driving up costs and urge Congress to “rein them in.”

Several of the pharma companies suing the government over the Medicare plan are ramping up their spending on federal lobbying, frequently mentioning the issue of drug price negotiations in their reports. Bristol-Myers Squibb has spent over $4.6 million through the second quarter, not far short of what it spent in the entirety of last year, and Merck’s $6 million in lobbying spending so far in 2023 is on track to match its highest-spending year in a decade. The pharma industry overall spent a record $372 million on federal lobbying last year—more than any other industry in D.C., continuing a decade-long trend of rising outlays on influencing lawmakers and policymakers.

Do we need any more reasons to vote Democrats from local to federal for the next generation or so?