The Fight for Lower Prescription Drug Costs Comes to Michigan

Legislators and patient advocates are racing to make Michigan the latest state with a board that can set upper payment limits on prescription drug prices.

By Paul Blest

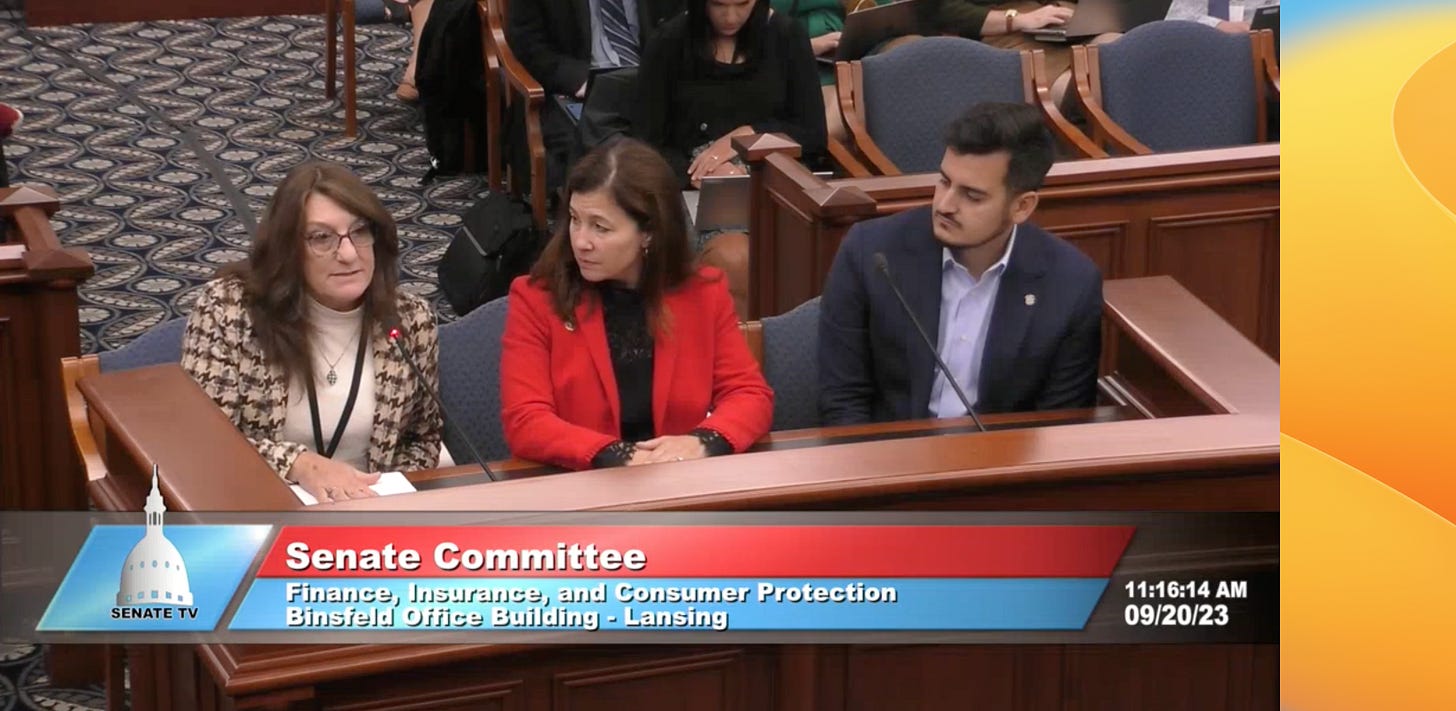

During a Michigan Senate hearing last month in Lansing, multiple sclerosis (MS) patient advocate Pete Rigney described rationing necessary medication in order to ensure he’d be able to keep taking it in an emergency.

Rigney counted himself among the 40 percent of people with MS who alter or stop taking their prescriptions due to high cost. While his insurance covers the $126,000 price tag of the Novartis-manufactured MS medication Gilenya, Rigney told lawmakers that he skipped enough days for a six-month emergency supply in the event he loses his job or his insurance is otherwise disrupted.

“Skipping doses of medication and making decisions out of step with my neurologist due to cost and not health outcomes should never be the norm,” Rigney told the Senate panel. “Every new lesion on my brain or my spine due to changes or lapses in treatment is irreversible.”

Rigney was speaking in support of a package of bills that would make Michigan the latest state to form a prescription drug affordability board (PDAB). A PDAB is a regulatory body not unlike a utility board, which has the ability to increase oversight over drug costs and establish upper payment limits, or the maximum amount that can be paid or reimbursed for a drug in order for everyone who needs it to be able to afford it. Eight states have passed laws forming PDABs in the last several years, five of which are empowered to set upper payment limits.

“The greed across the system at the expense of our health and livelihoods must stop,” Sen. Kristen McDonald Rivet, one of the senators who introduced the proposal, said during the Senate hearing last month. “The strength of a public board is its intention of centering and raising the voice of our residents as the most important influence in the policy we make. This board does just that.”

The Michigan Senate passed SB 483 and two related bills earlier this month after Gov. Gretchen Whitmer endorsed the creation of an affordability board in August, and the proposal is backed by groups including the AARP and the Committee to Protect Health Care, a nonprofit patient advocacy group founded by medical professionals. But the bills now have to clear the House, which — like the Senate — has a slim Democratic majority.

On top of that, the bills are facing strong pushback from pharmaceutical companies, which have brought in record profits since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pharmaceutical industry trade group PhRMA is lobbying against the proposal with paid ads claiming a PDAB will unnecessarily interfere with the doctor-patient relationship, prompting the Committee to Protect Health Care to release a letter this week from more than a hundred Michigan doctors in support of the PDAB proposal.

“Let's be real, the real issue impacting our ability to prescribe medications is the cost set by pharmaceutical corporations,” Dr. Rob Davidson, the Committee to Protect Health Care’s executive director and an emergency room doctor in western Michigan, said during a virtual press conference Monday. “We're not surprised that PhRMA is using money and scare tactics to try to protect their massive profits, but for them to do so under the guise of doctors is reckless and wrong.

“Make no mistake, doctors support creating a prescription drug affordability board because it will work for our patients,” Davidson said.

Skipping doses

Exploding prescription drug costs have hit patients suffering a broad variety of illnesses. Between 2016 and 2022, the increase in cost of more than 1,200 drugs exceeded inflation, with an average increase of more than 30 percent, researchers from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found.

As part of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, Congress empowered Medicare to negotiate directly with drug makers, and in August, the administration chose the first ten drugs for the negotiations. The companies that produce those medicines agreed to negotiate earlier this month, though some of them are still suing the administration to block the new law.

Davidson recalled treating a patient in his emergency department who had been seen weeks prior with a blood clot in their leg and prescribed Eliquis (one of the medicines selected by the Biden administration) to treat it. But because the cost of the prescription was hundreds of dollars, Davidson said, the patient chose not to buy it, figuring they could figure something out with their doctor later.

“In the meantime, the blood clot broke off, went to [the patient’s] lungs, and they ended up getting admitted to the ICU,” Davidson said.

The proposal put forward by the Michigan Senate would allow the governor of Michigan to name five members for the board “who have expertise in health care economics, health policy, health equity, and clinical medicine,” subject to confirmation by the Michigan Senate. The board would be advised by a “stakeholder council” made up of 21 representatives from healthcare companies, medical professionals, and advocacy groups.

“Every day, we hear terrible stories of people having to ration their medications or skip doses because their prescriptions are just too expensive,” Sen. Darrin Camilleri, one of the package’s three primary sponsors in the Senate, said in a statement following its passage.

“By creating a nonpartisan Prescription Drug Affordability Board, we have an opportunity to address rising drug costs and make sure all Michiganders can afford their medications.”

‘Gaming the system’

The bills have been assigned to the House Financial Services and Insurance committee, which has not yet taken them up. Davidson told More Perfect Union Tuesday that he’s “hopeful” the package will receive a hearing and a floor vote in the next several weeks.

Rep. Carrie Rheingans, who introduced her own bill this year to lower prescription drug costs and another that would create a publicly funded healthcare system, told More Perfect Union that “gaming the system” in the pharmaceutical patent process has been one contributor to high costs for patients.

Rheingans told More Perfect Union that “people like Michiganders really want something to be done about the cost of healthcare in general, and prescription drugs specifically.” But there are some concerns in the House about the lack of hard evidence showing PDABs lower drug prices, she said.

A big reason for that is that none of the PDABs around the country have fully operationalized to the point where they’ve set upper payment limits on any drug yet. Maryland passed the first PDAB with the authority to set upper payment limits back in 2019, and the board is still working on doing so, with an additional effort coming in the legislature next year to grow the board’s authority to include private insurance plans. (Currently, their authority is limited to state and local government insurance plans.)

The closest is in Colorado, where iIn August, regulators launched affordability reviews into five drugs, including medications that are commonly used to treat cystic fibrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and HIV.

“Personally, I know PDABs are popular, and I feel like there's a way to make it work,” Rheingans said. “So somehow, we need to just figure out how to make it work for us here in Michigan.”

Patients like Rigney are counting on that, as he told lawmakers during the Senate hearing.

“Medication cannot improve lives unless people can afford to access them,” Rigney said.

#UniversalHealthcareNow !!!!!