Justice Department Data Contradict Retailers' Organized Theft Claims

In many large U.S. cities, shoplifting rates are below pre-pandemic levels. But theft still has a big impact on industry profits, and the data remains murky.

By Eric Gardner, More Perfect Union

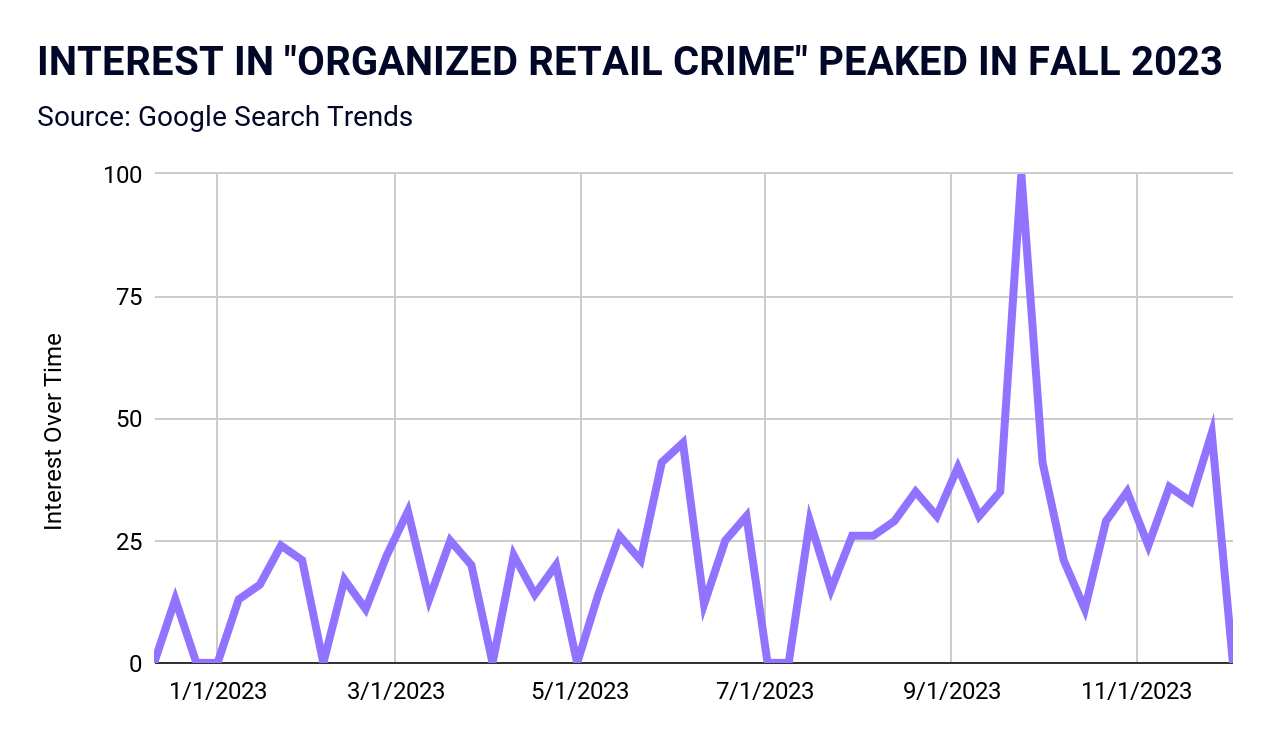

Retailers, their lobbying groups, and both national and local media outlets have endlessly reported an epidemic of shoplifting over the past few years. Google search interest in organized retail crime soared over 300 percent this fall, reflecting widespread perception about systemic and organized shoplifting across America.

But a new Council on Criminal Justice study challenges this story. Analyzing Justice Department data from 24 large American cities, the authors found that shoplifting largely mimicked pre-pandemic levels, with most incidents involving only one or two individuals. Despite an increase in viral footage, large-group cases are extremely rare.

“Shoplifting generally followed the same patterns as other acquisitive crimes (except motor vehicle theft) over the past five years,” the authors concluded.

The study starkly contrasts the narrative of the National Retail Federation (NRF) and the Coalition of Law Enforcement and Retail (CLEF). Since at least 2016, these two groups representing America’s largest retailers have published research arguing that America’s big box stores were losing upwards of $40 billion a year through organized crime rings pilfering large quantities of merchandise from stores and selling the goods online.

The research became a popular narrative, finding its way into features across the mainstream media, including the Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, New York Times, and even congressional testimony. Target, which has faced significant investor pushback over poor financial performance related to subpar inventory management, used it as a pretext to close stores. Last week, the NRF retracted the findings after Retail Dive, an industry publication, found significant discrepancies between the data and reality.

“While theft is likely elevated,” an analyst from William Blair wrote in a client note, “companies are also likely using the opportunity to draw attention away from margin headwinds in the form of higher promotions and weaker inventory management in recent quarters.”

The challenge lies in the lack of clear metrics. While America does capture data on retail crime, the statistics aren’t comprehensive enough to make clear-cut pronouncements about the issue. Even the aforementioned data analyzed by the Council on Criminal Justice is helpful but not definitive. It’s based on reported DOJ statistics around shoplifting or theft without delving into whether these incidents are part of larger, organized criminal operations.

The retail industry’s data also isn’t super illustrative. It has long bucketed shoplifting under the measure “shrink” in public reports. In the retail industry, “shrink” typically accounts for all unsold inventory, including outside theft, employee theft, and damaged or lost goods. So, although it is often used as shorthand for theft, it’s not, as Walmart CEO Doug McMillion recently clarified. “Shrink is comprised of more than one thing,” McMillion said during an August call with investors.

Just last quarter, the grocery giant Kroger told Wall Street it reduced shrink by using technology to manage fresh product spoilage better—a far cry from any type of crime prevention. That’s not to say that theft and other “shrinkage” aren’t serious issues that can impact a company’s bottom line and sometimes endanger workers. It's thought that shrink is typically split evenly between traditional theft, employee theft, and operational mishaps—but this is more of an estimate than a strict rule.

For instance, Target reports shrinkage at just below 1 percent of total sales. While this might seem small, it's substantial for a company of Target’s size. In the first three quarters of the year, the Minnesota-based giant experienced about $670 million in shrink, or roughly $223 million of traditional theft. If this loss were converted into sales, Target's operating profit would increase by 6 percent, above $4 billion.

This increase is partly linked to a major shift in retail operations, namely self-checkout.

Many retailers have replaced cashiers with self-checkout systems over the past decade, looking to reduce labor costs. However, this change led to unintended outcomes, notably higher theft rates. One study saw theft rates double at stores with self-checkout. A specialist told CNN that a store with 50 percent of its transactions through self-checkout could see losses 77% higher than usual.

Retailers seem to be catching on. Best Buy, which hasn’t seen theft impact profits, plans to add more workers and full-service check-out lanes proactively. Target is testing new self-checkout policies. Dollar General, known for inadequate staffing and self-checkout, is committing $150 million to move away from the technology.

“We had relied too much on self-checkout in our stores this year,” Dollar General CEO Todd Vasos said in the most recent earnings call. “We should use self-checkout as a secondary checkout vehicle, not a primary.”

Despite retracting earlier statistics, the NRF, which has lobbied Congress for a retail crime bill, continues emphasizing the impact of organized retail theft.

“We stand behind the widely understood fact that organized retail crime is a serious problem impacting retailers of all sizes and communities across our nation,” a spokesperson for the group told Digital Commerce 360 last week. “At the same time, we recognize the challenges the retail industry and law enforcement have with gathering and analyzing an accurate and agreed-upon set of data to measure the number of incidents in communities across the country.”

My gut was telling me that retail theft was not the real reason behind stores closing. The big retailers have to have a story to tell their investors. I'm wondering if anyone is looking at the impact Amazon is having on these stores, as well.