In This Town, Only the Rich Get Water

A massive dairy operation is thriving using Arizona groundwater. In a nearby town, working people’s wells are drying up.

By Katie Nixdorf, More Perfect Union

Residents in Pearce, Arizona are facing a dystopian crisis: their wells are running dry while a neighboring industrial dairy operation continues to use unprecedented amounts of groundwater.

Over the past 10 years, Riverview, a Minnesota-based dairy company, has spent more than $160 million buying up land in Cochise County, near the state’s southeastern border with New Mexico.

This transformation has come at the cost of water for residents like Vance Williams. He lived in Pearce for six years before his well ran dry in 2020, leaving him without running water in his house for six months. He was forced to buy five-gallon jugs of water to use for dishes, laundry, and showering while he saved up to put in a $3,000 water tank.

“Getting this set up and running took every penny I had extra and some that I didn't,” said Williams. “Some of it went on the credit cards.”

More Perfect Union went to Pearce last month to see how the fight over who gets to control our most essential resource is playing out—and how a new bill could put power back into the hands of residents.

Watch our full report:

Deep wells and deeper pockets

Arizona started monitoring water levels in 1980 after state lawmakers passed the Groundwater Management Act. It was landmark legislation that finally put conservation laws in place, but there was a catch: the law excluded rural areas—roughly 80 percent of the state.

That’s how companies like Riverview can pump as much water as they want.

Before Riverview came to town in 2014, the dairy farm here used about 61 million gallons of water per year. By 2022, Riverview’s massive operation was using roughly 900 million gallons—and that doesn’t even include the water it takes to grow all of the feed.

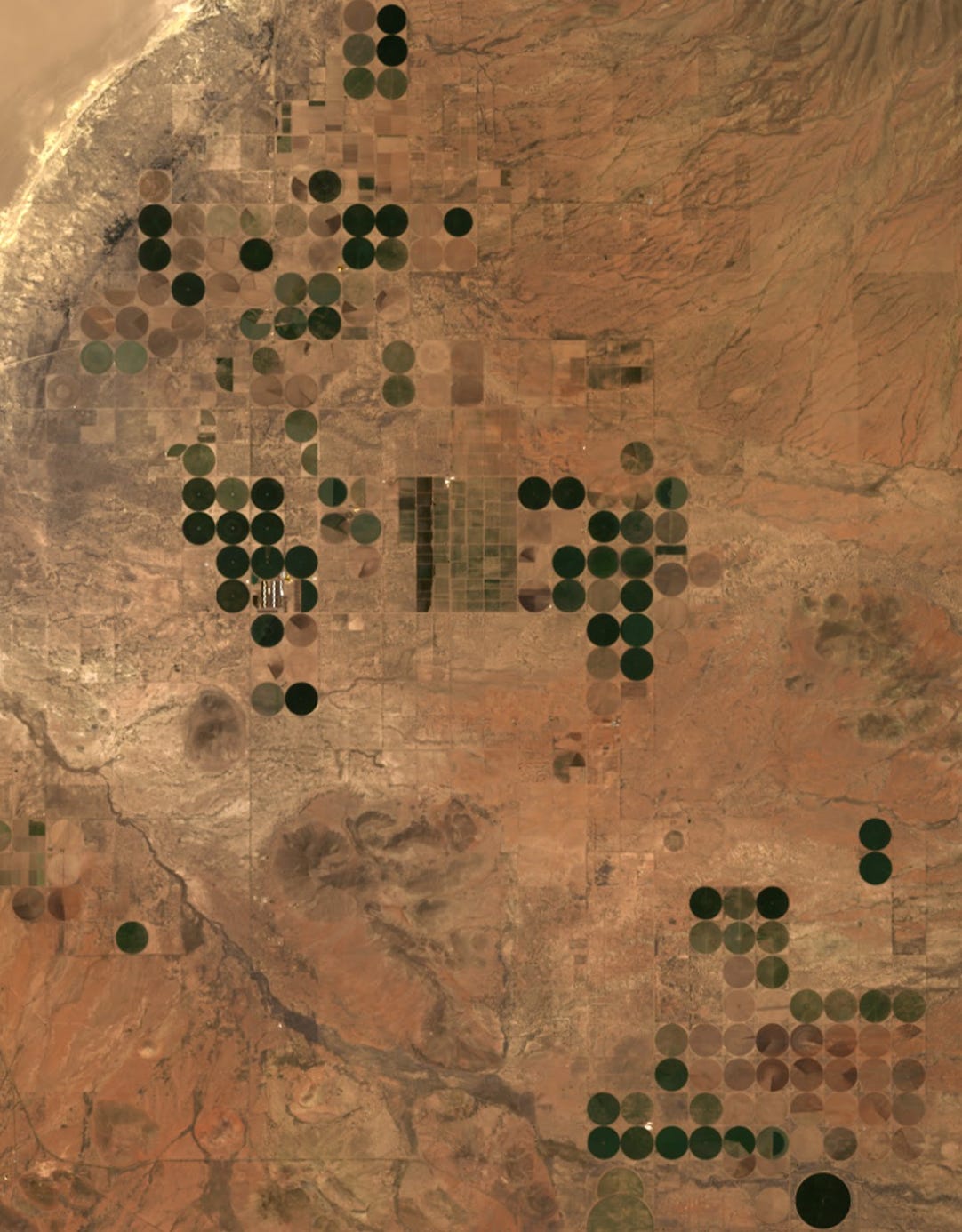

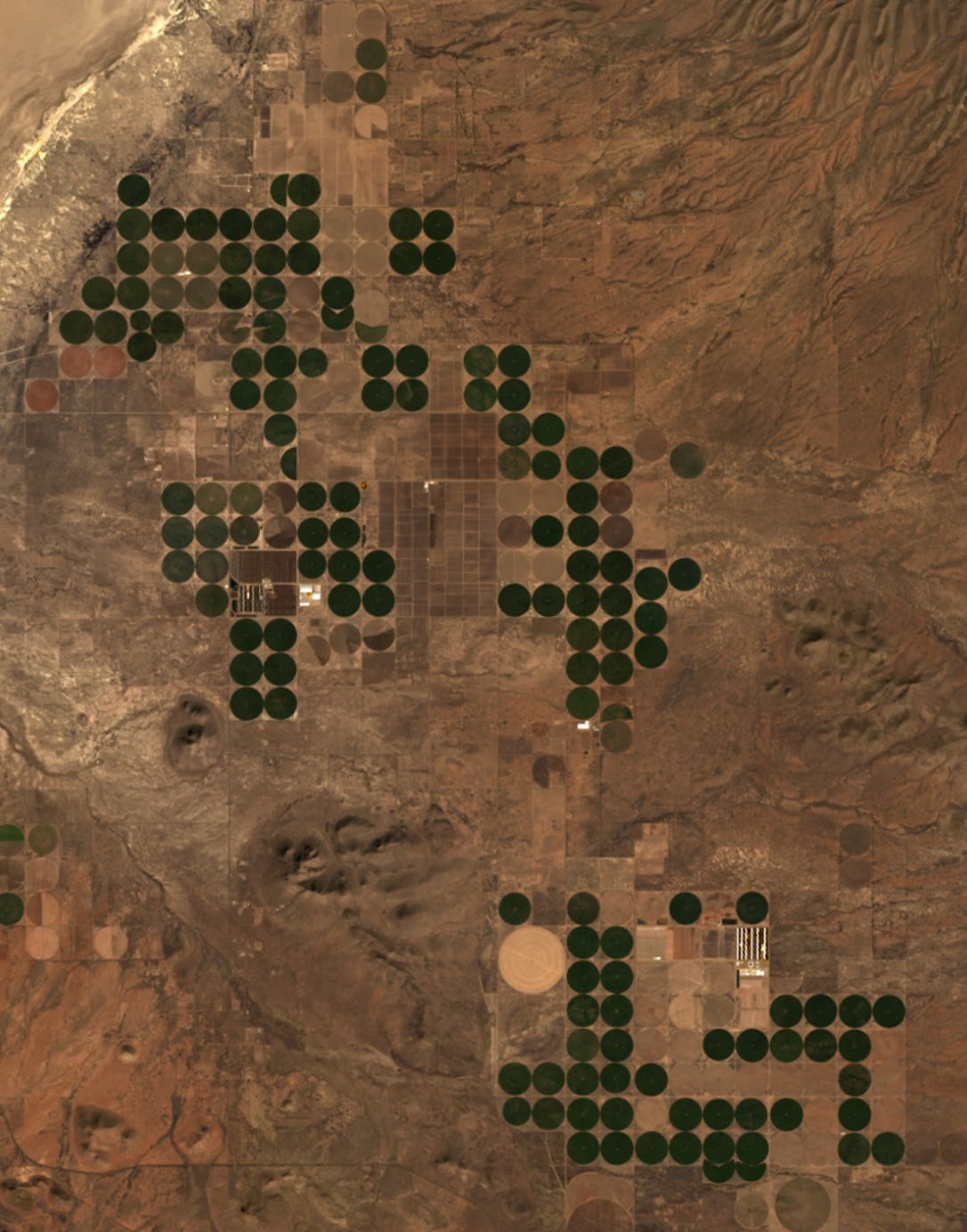

Satellite images show the farm’s growth from 2013 (top) to 2022.

These vast green fields are mostly corn, hay, and alfalfa harvested as silage to feed Riverview’s cattle. Riverview’s total water use, including the water it takes to grow crops and run the dairy, is estimated at 35 billion gallons, or enough to fill more than 40,000 swimming pools.

Groundwater levels here declined by an average of 2.7 feet per year between 2000 and 2020. This extensive water use is impacting the entire water table so much that the land itself is sinking by about 2.5 to 4 inches per year in a process known as land subsidence. “For it to subside at the surface it has to be systemic. It has to be across the entire basin,” said Ryan Mitchell, the chief hydrologist for the Arizona Department of Water Resources. “So to me, that is alarming.”

But even as water levels reach crisis levels, some people have more access than others. The average residential well is about 409 feet. Drilling even a few hundred feet deeper is cost-prohibitive for most residents, but Riverview has wells that extend up to 2,710 feet into the ground.

“So that is where the advantage lies with the people who have the deep enough pockets to drill deep wells,” said Mitchell.

In 2022, Vance talked to a news outlet about his experience losing water. Shortly after, Riverview paid to deepen Vance’s well. The total cost: $37,795.

“[Riverview] just threw money at it. Money that none of us out here have,” said Williams. “My well is worth more than my house right now. How do you justify that?”

Many residents have no choice but to leave this area. “I'm leaving because I can't watch this anymore,” said Traci Page, whose well dried up in July 2023. She had to sell her tractor and part of her gun collection to save up the $16,000 she needed to deepen her well. But even with a deeper well, she doesn’t see a future here.

“I get that some of it's nature. I get I move to the desert, I get it. But this state is mismanaged. They're allowing people with the most money to do whatever they want.”

A statewide crisis

Riverview isn’t the only company taking advantage of Arizona’s extremely lax regulatory environment. Perhaps the most high profile is Fondomote, a Saudi Arabian farm growing alfalfa and shipping it overseas. Governor Katie Hobbs (D-AZ) terminated a lease between the state and the company last year, and Fondomonte has now ceased operations on that land.

But Fondomonte still owns several thousand acres of land in the state, as do other companies like Water Asset Management, a New York-based investment firm, and Greenstone, a subsidiary of the billion-dollar insurance giant MassMutual.

That’s why Hobbs is gunning for a longer-term solution. In 2023, she formed a Water Policy Council of farmers, environmentalists, legislators, and tribal communities. Their task was to come up with a framework for rural groundwater management.

It hasn’t been a seamless process—state Senator Sine Kerr (R-AZ) and Stefanie Smallhouse, president of the Arizona Farm Bureau, quit the council, claiming it was driven by “progressive environmental goals of special interest groups.”

Kerr went on to create her own bill, SB 1221, which makes groundwater management possible only through a complicated process that critics say would be nearly impossible to execute. Four Arizona County Supervisors have argued it “does not address or adequately minimize the precise reason we are in these situations in rural Arizona.”

The recommendations from the Water Policy Council, however, were used to craft a different bill, HB 2857. If passed, this bill would create a framework where resident-run councils decide water regulations, which could be anything from incentives for more efficient irrigation to stringent policies that limit water use.

“That local control is a huge part,” said Ed Curry, a fourth-generation chili farmer who served on the Water Policy Council. “It lets us kind of guide our ship.”

Curry hopes the plan is something that will draw bipartisan support. “I hope that 100 years from now, they know that we were right,” said Curry. “That this valuable desert, one of the last strongholds of water in the whole southwest, came up with a bipartisan agreement. That everybody came together, out of care and concern for one another.”

For working people like Vance Williams, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

“Somebody’s gotta decide that people are more important than money,” he told More Perfect Union. “The people that are responsible, or should be doing something that aren’t, I personally think they all need to live off of five-gallon jugs of water for a while and understand how devastating that is to somebody that thought they had a forever home.”