Biden Asserts Power to Seize Drug Patents — What Comes Next?

An initial target could be Keytruda—the $200,000 wonder drug for cancer patients that was developed using taxpayer dollars.

By Eric Gardner, More Perfect Union

The Biden administration recently announced a plan to lower drug prices and increase competition in the industry by asserting its authority to take over the patents of costly drugs that were developed with federal funding.

“In my opinion, it is one of the most potent tools that the federal government has to help lower the cost of prescription drugs using the authority that's already available to the government,” Bharat Ramaurti, the former Deputy Director of Biden’s National Economic Council, told More Perfect Union.

This power, sometimes referred to as “march-in” authority, rests in the Bayh-Dole Act, a 1980 law that permits companies to profit from publicly funded scientific discoveries. It contains a provision central to the administration’s strategy that allows the government to authorize other companies to use these patents under certain conditions. Under the new Biden framework, federal agencies can exercise this power based on the price of a drug—a strict reversal from the Trump administration, which proposed banning the government from considering price when making march-in decisions.

One of the first targets of the new authority could be the world’s highest-grossing cancer drug: Keytruda, manufactured by pharma giant Merck.

Keep reading below, or watch our new feature on Keytruda and pharma patents here:

Keytruda is as revolutionary as it is costly. The drug trains the body’s immune system to attack cancer cells. When used with regular chemotherapy, it increases the survival rate of lung cancer patients to 40%, compared to only 5% with standard treatments. Merck currently charges nearly $200,000 for a year of treatment.

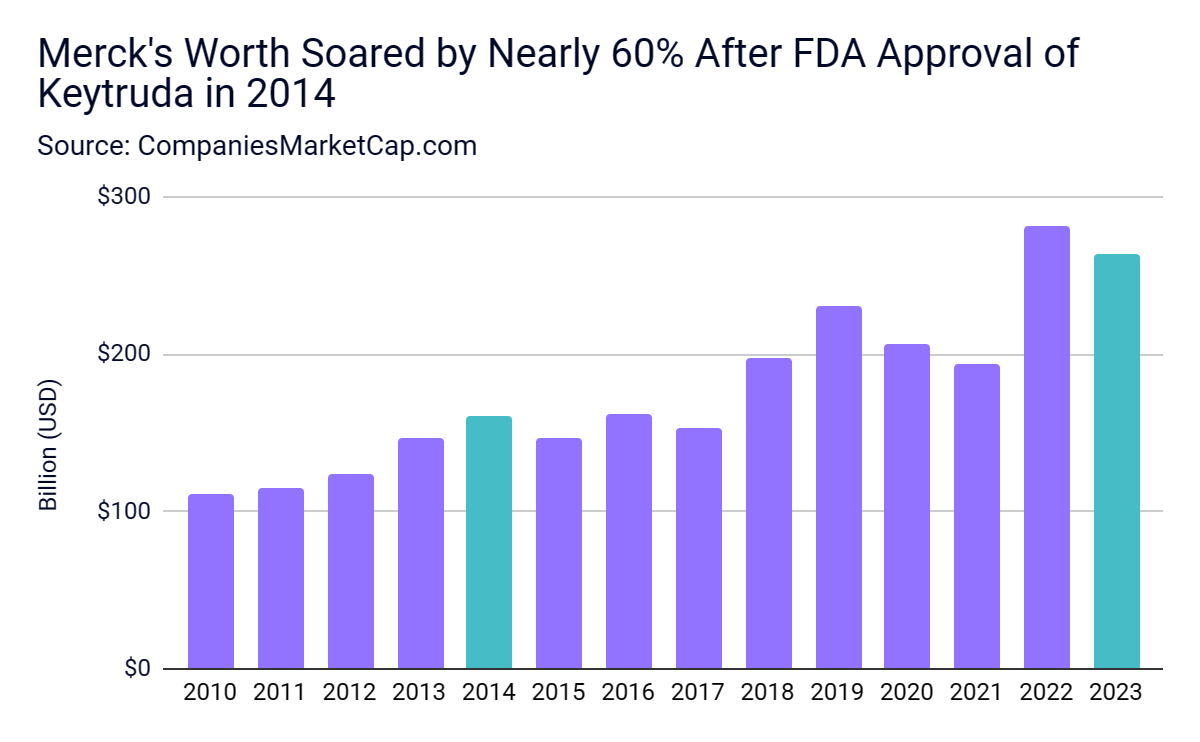

The high price tag fueled massive sales and almost single-handedly re-established Merck as a pharmaceutical titan. In 2022, Merck sold $52 billion worth of prescription drugs; Keytruda accounted for nearly 40% of that. Since Keytruda was approved in 2014, Merck's market value has ballooned, making it one of the 50 most valuable companies in the world.

The high cost of groundbreaking drugs exerts significant pressure on the healthcare system. “It raises the cost of insurance premiums,” Jamie Love, the Director of Knowledge Ecology International, a nonprofit focusing on intellectual property's impact on social justice, told MPU. “It raises taxes if you pay for it through Medicare or Medicaid.”

Currently, prescription drugs account for one-fifth of insurance premium expenditures, a proportion growing faster than any other medical expense. This escalating burden raises questions about the traditional business model in the pharmaceutical industry, where large profits are seen as essential for fostering innovation and discovery.

Keytruda suggests a more complex reality.

Despite the narrative of private sector-led development, Keytruda’s foundation rests on research funded by the federal government, which resulted in six critical patents. "The early development was done primarily in academic institutions and was funded by governments and charities,” Love said.

Under the Biden administration’s new guidance, the government could use the $200,000 annual price and the fact that federal resources contributed to the research as justification to “march in” and open up those six patents to competition. According to Ramaurti, the government could “license that patent to some other company or nonprofit entity that could charge far less for that product.”

The policy is predictably not without its detractors. The WSJ published an editorial lambasting the decision. PhRMA, the industry lobbying group, added, “This would be yet another loss for American patients who rely on public-private sector collaboration to advance new treatments and cures.”

Last year, PhRMA spent $29 million lobbying the federal government and trying to stop one of the Biden administration’s crowning legislative achievements: allowing Medicare to negotiate the price of some drugs it buys. Other countries already have that ability. In 2018, the United Kingdom’s drug pricing board negotiated a rumored discount on Keytruda of up to 50%.

Patents grant their holders exclusive rights to manufacture and sell drugs. After 20 years, the patents are opened to generic competition, which drives prices down. March-in rights, or simply the mere threat of their enforcement, could threaten a growing pharmaceutical industry business strategy. It's called a patent wall—turning patents, not innovations, into profit machines.

A striking example of this strategy was seen with the popular arthritis drug Humara. In 2016, the key patents were set to expire, opening it up to competition and lowering prices. Btut the company behind the drug filed several patents that pushed the patent date back. This allowed the company to increase the price to $80,000, generating $114 billion in profits.

Merck adopted a similar approach with Keytruda, obtaining nearly 130 patents to prolong its exclusivity beyond the original 2028 patent expiry. A Merck executive openly acknowledged this strategy in 2021 when answering a question about the drug’s upcoming patent expiration: “We do think there may be some opportunity beyond that time frame as we move forward.”

Using march-in rights could help bring down the patent wall, allowing companies to bring drugs covered by those six patents to market at lower costs. But whether it will remains to be seen: The National Institute of Health has never exercised march-in rights on a drug’s patents.

“The question is gonna be,” Ramaurti concluded, “are they actually gonna use the authority that they've now granted themselves to march in on a drug or not?”

Socialism for the rich, par for the course. These drugs were paid for by federal grants through NIH and NSF, as well as money given to universities for building construction. If you ignore that you're either stupid or a paid liar.

On the one hand, it seems obvious that the profit motive could incentive companies to innovate and make better drugs. On the other hand, corporations want to keep shareholder profits flowing, FOREVER, and have a near zero incentive to cure people. The more drugs we make, the more illness that said drugs treat we get. Pharma Corporations are richer than ever and Americans are sicker than ever. Doesn't seem like the system is working.