‘Are We Going to Have Running Water?’ Inside the Dismantling of Alaska Public Schools

Years of funding shortages have brought Alaska’s once-great public school system to the brink of collapse—and a right-wing governor is standing in the way of fixing it.

By Nicole Bardasz, More Perfect Union

Public schools in Alaska are crumbling, literally and metaphorically.

Alaska’s traditional public schools have dropped into the bottom five worst-performing in the nation. Only 27 percent of third graders are reading at grade level, and 500 teacher positions across the state — out of about 7,500, according to the National Center for Education Statistics — were vacant at the start of the school year.

Then there are the school closures. Fairbanks, the third-largest city, has closed down three schools over the past two years, and another will shut down this year. Juneau, the state’s capital, announced that it will consolidate its middle and high schools to help reduce the district’s $9.7 million budget shortfall. Anchorage, the most populous city in the state, just said it will announce a “multi-year” school closure and consolidation plan this fall.

As for the schools that remain open, many are in a state of disrepair. School maintenance issues have piled up for years, without adequate funding to address them. Districts are left wondering whether they’ll have the bare necessities.

“Are we going to have running water and functioning sewer systems? Are we going to have buildings that are not condemned? Ones with operational fire panels?” asked Haines Borough District Superintendent Roy Getchell, whose district serves between 250 and 300 students in southeast Alaska.

These problems are particularly severe in rural Western Alaska. In Sleetmute, the school’s roof is in “imminent danger” of collapsing on one side, forcing students and teachers to hold classes on the other side of the building, Superintendent Madeline Aguillard told the Anchorage Daily News. There’s nowhere else for them to go.

This is the result of years of stagnant education funding from the state, which has not come close to keeping pace with inflation. Districts in the three largest cities in Alaska face a multi-million dollar budget shortfall; hundreds of additional teachers could be furloughed or laid off and more schools could close.

The good news is that some help is on the way. The state legislature just approved a $552 million capital budget, which would raise spending on school maintenance to the highest level since 2011. And lawmakers also approved a one-time, $175 million funding boost for public schools, which would increase the spending per student, also called the Base Student Allocation, by $680.

The bad news is that it’s not nearly enough — and the state keeps drifting further towards Gov. Mike Dunleavy’s not-so-secret vision of privatized public education.

The worse news is that Alaska mirrors a growing national crisis in neighborhood public schools.

‘We’re just not competitive anymore’

Schools across the United States are facing the crunch of skyrocketing cost of living, lack of funding, and a worsening teacher shortage. But as is often the case, because of Alaska’s high cost of living, it is feeling the consequences of the crisis more acutely. During the 2021-2022 school year, the U.S. lost 10 percent of teachers nationwide, but Alaska lost more than double that.

“There was a time when we were the highest paying state and the [best] funded state in the country,” said Getchell. “And that’s why we would have far more applicants than we did positions.”

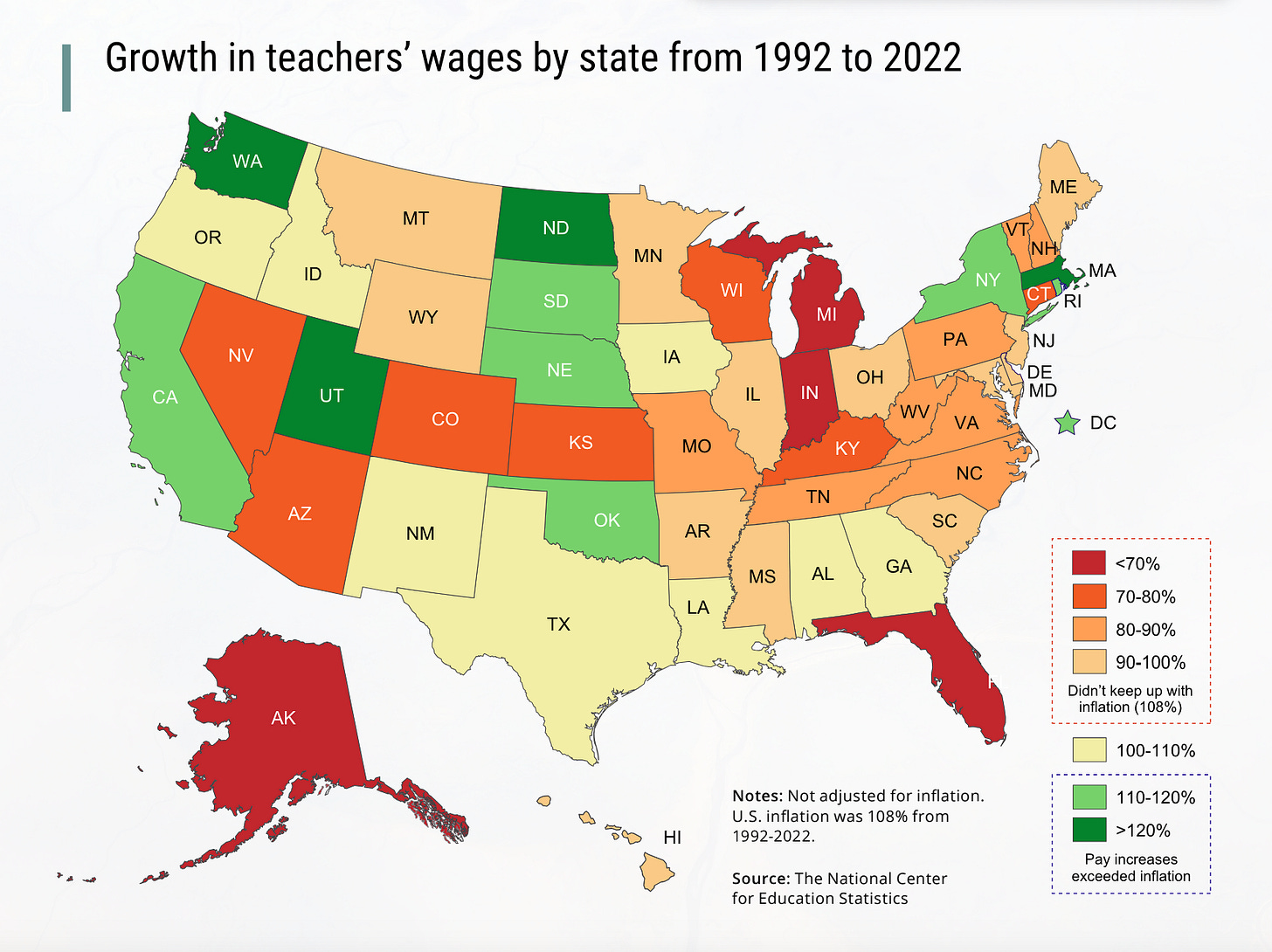

As recently as the 1990s, Alaska offered the highest average salaries in the country for K-12 teachers, according to a report in Alaska Economic Trends Magazine. But over the past two decades, Alaskan teachers’ inflation-adjusted wages have fallen more than 4 percent.

“We’re just not competitive anymore,” Getchell said.

Education advocates, superintendents, and others point to flat education funding as a major root cause. When adjusted for inflation, Alaska’s base student allocation (BSA) — how much the state pays schools per student — has dropped $1,229 since 2017, a 17 percent decrease.

The Alaska state legislature, to its credit, heard the cry. In March, the House and Senate overwhelmingly passed a long-term funding boost for public education that would have changed the per-pupil funding formula and permanently allocated $680 more per student. It sailed through both chambers with broad bipartisan support, and while it fell short of the $1,413 per student that advocates hoped for, it was praised as a major step towards addressing the state’s education crisis.

Then Gov. Dunleavy vetoed it.

“While I support the basic idea of education funding reform, this bill fails to address the innovations necessary to allow Alaskan students to excel,” Dunleavy wrote in his veto message. “Charter schools are an innovative and proven alternative to traditional education for many children. Education reform is more than funding. True reform must embrace a willingness to provide alternative methods of education to meet the varying needs of our student population.”

It wasn’t unexpected — Dunleavy last year halved the one-time $680 increase to the BSA the legislature put on his desk. This time, he vetoed the funding plan because it lacked two provisions he had asked for: giving cash bonuses for certain qualified teachers, and moving control of charter schools to the state board and away from local districts.

The state legislature failed to overturn the veto and instead approved a one-time, $175 million funding boost to the BSA, which Dunleavy signaled his support for. (After vetoing the long-term funding, Dunleavy commissioned a poll, which unsurprisingly showed that Alaskans overwhelmingly support increasing education funding.) It also included an additional $5.2 million for a controversial and experimental reading academy championed by Dunleavy.

Lawmakers additionally approved a $552 million capital budget, which would bump the state’s spending on school maintenance to the highest total since 2011.

Superintendents who spoke to More Perfect Union were appreciative of the funding increases, but expressed concern that they didn’t go nearly far enough to address the scale of the problem. Aleutian Region School District Superintendent Mike Hanley called the one-off funding a “band-aid.”

“One-time funding can’t be put into long-term budgets for a district and speaks to the governor’s and legislature’s unwillingness to commit to funding a basic responsibility in our state,” Hanley said.

Yupiit School District Superintendent Scott Ballard, whose district serves 445 mainly Alaskan native students in the remote Bethel area, told More Perfect Union that the one-time funding will allow the district to continue for another year, albeit with job cuts and restrictions on preventative building maintenance.

“School districts around the state essentially are in fiscal limbo every year, unable to determine their ability to retain staff, and pay their bills for electricity, heating oil, liability, and property insurance, as well as maintaining buildings and equipment,” Ballard said.

Roy Getchell, the Haines superintendent, compared the one-time $680 boost to a “one-time grant.”

“It’s enough to get by. It’s enough to have a school,” he said. “But even today, not knowing that it’s going to be there, I can’t plan for that next year. I can’t, on May 15th, plan for August 15th, because I don’t know how much I’m going to get.”

‘Private school, state reimbursement’

There’s an even bigger threat to Alaska’s public education system lurking in the debate over school funding: school privatization. Where Dunleavy has failed to secure healthy and stable financing for public schools, he’s excelled as a champion for charter and private schools. For over a decade, he’s worked to increase the number of charter schools in Alaska and grow their resources.

Unlike other red states in the lower 48, Alaska has never had a voucher program to fund charter schools or private schools. In fact, the state constitution expressly states that “no money shall be paid from public funds for the direct benefit of any religious or other private educational institution.”

That did not stop Dunleavy from trying to create his own voucher system in Alaska. Alaska has had a correspondence, or homeschool, program, since before statehood. In 2014, then-state Senator Dunleavy introduced and passed into law an expansion to the program providing families an allotment to “purchase nonsectarian services and materials from a public, private, or religious organization.” The money for the allotment comes from the student’s affiliated public school district.

If Dunleavy’s intentions weren’t clear enough, his political ally Jodi Taylor (wife of Alaska Attorney General Treg Taylor, and chair of the conservative Alaska Policy Forum think tank) published a detailed guide, titled ‘Private School, State Reimbursement,’ about how to use the allotments for private schools.

In early 2023, families supported by the National Education Association of Alaska, the union that represents more than 12,000 educators in the state, filed a lawsuit alleging that the use of correspondence program allotments for private schools was unconstitutional. In response, the Betsy Devos-backed libertarian law firm Institute for Justice recruited a group of Alaskan families who benefit from the program to file a countersuit.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because it’s almost the exact playbook that right-wing groups, including that same Institute for Justice, ran in Arizona starting in 2006. The Arizona Supreme Court ruled their voucher program unconstitutional in 2009, but it wasn’t long before they found a loophole.

“[The courts] said, ‘we can’t give public dollars straight to private schools. There’s a violation of the separation of church and state,’” explained Save Our Schools Executive Director Beth Lewis. “So special interests took those court orders… and said, ‘so what if we just give the money to the parents, then we’re fine, right? They can send it to the private school.’”

After Arizona lawmakers passed a voucher law in 2022, the state’s Education Savings Account program quickly ballooned, siphoning money directly away from Arizona’s public school system. Students in public schools are already facing funding shortfalls while private schools and charter schools are free to operate discriminatory and for-profit grifts.

Anchorage Superior Court Judge Adolf Zeman struck down Gov. Dunleavy’s allotment program last month, but the case is not yet settled; it’s likely that either the state or the Institute for Justice will appeal to the state Supreme Court. And in the interim, the governor seems content to deprive Alaska’s public schools of the consistent funding they need to stay afloat—let alone thrive.

“I think that Alaska really needs to work on a vision for who we want to be as educators, who we want to be as a state, and what we want for our children,” Getchell said. “I don’t want to use a worn-out playbook from the rest of the lower 48. I don’t want to go down that road.”

“We have to figure out what’s going to work for our state, what’s going to be the best benefit for our students, and then do it.”

Republicans want uneducated people. They ascribe to the “Mudsill Theory “ that their position is built on a group of uneducated workers who are stuck in low paying jobs or actual serfdom or slavery which supports the Rich. This group is controlled by religion, superstition and onerous laws with powerful enforcement. Thom Hartmann has a great article on this.

Iowa is another state depriving public school of funds over to private schools. How many states are doing this? I think Texas & Florida are 2 others with this hairbrained idea.